When to Punch:Process capabilities, speed, operating cost, and customer preference count

source:

keywords:

Time:2016-06-28

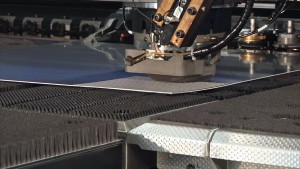

In many cases, a customer will present a drawing for a sheet metal part for which either punching or laser cutting can produce the holes and perimeter. If the part has formed features, choosing punching would most likely eliminate secondary operations that would be necessary if it were cut on a laser.

Deciding what goes to punching is always application-specific and often depends on customer desire.

There are, however, definite considerations to help determine when, and why, punching will be the best technology to produce a part at the lowest cost for the customer and the highest profit for the shop.

evaluate Operating Costs

Using a laser is often considered simpler than running a punching machine because only one tool–the laser beam–can create all shapes and sizes. But that flexibility comes at a cost. The initial equipment investment and the overall operating costs are higher than those of a punching machine.

The laser draws more electricity and needs assist gas. For example, a fiber laser may use over 1,000 cubic feet of nitrogen to cut at high speeds, which can add $10 to $12 per hour to the process cost.

When punching, there is really only one cost–the cost of the electricity–which is typically less than half of that required by the laser. This is why operating costs for punching will always be less. The impact of these factors on job estimates makes them incredibly important in selecting a production process.

Another factor is production speed. A laser may be able to cut the holes in a part in 30 seconds but the punch can produce the same holes in about half the time. If a part is perforated or has a lot of holes, say up to 30,000 holes, punching will produce two parts to a laser’s one. Throughput often can be increased further by using a cluster punch.

The punch will most likely require more setup time than the laser. That’s where batch sizes come into play. If you need to produce only one or two parts or a very small batch, the laser might be the more attractive approach because changeover from one job to another will be faster. But as batch sizes increase, the savings of a few seconds per part add up quickly and make punching the best alternative.

Analyze the Part

As a rule of thumb, quality parts can be produced on a punching machine from sheet metal that is 10 gauge or less. Material on the thin side can be punched as long as it can be held so that it maintains its rigidity when it’s moved during the punching process.

Thicker material can certainly be processed by a punch, but there will be a differentiation from cut to break in the walls of the punched feature. Side-wall angles typically will be a little less when punched than you’d see from a laser, but essentially the quality will be comparable.

The size of hole that can be punched depends on the thickness of the material and varies depending on the equipment. In general, the ratio is 1-to-1. Some machines are capable of punching a 1/8-in. round hole in ¼- in. material.

Rectangular parts, which many sheet metal parts are, are perfect candidates for punching. Large, round parts or parts with strange, complex contours are going to be well-received as laser parts, however, as long as some slight overlap marks are not a problem a punch can nibble large openings or irregular shapes.

An important factor in deciding to use punching is its forming capabilities. Parts that have louvers or countersinks or that need tapping are great candidates for the process. Formed features can be completed and taps can be added in one operation with one setup. Processing time is reduced, secondary processes and their setup time are reduced or eliminated, and the possibility of error–which increases as a part moves from station to station—is reduced or eliminated.

Factor In Tooling and Automation

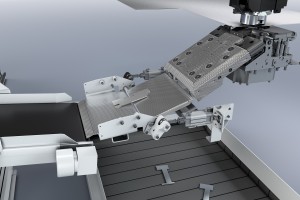

A part can have a virtually unlimited number of hole sizes, shapes, and placement within a part. A automatic tool changer and carousel, typically with 15 to 60 tools, provides the capability to punch a variety of holes without reloading tools, but the key consideration in having true punch flexibility is the machine’s ability to rotate each tool 360 degrees.

That rotational ability tremendously expands the number of punched patterns that can be produced without additional setup or investing in additional tooling.

Rotational tooling also allows parts to be nested on the sheet at any angle for efficient material utilization. Scrap percentage goes down along with the final per-piece part cost.

once a part is complete, punching machines can offer expanded options and often a more effective means of sorting parts, for example, down a chute or with an automatic unloading device with suction cups, again adding to a faster, more efficient process for large batches.

The width of the punched perimeter allows parts to be completely separated from the sheet for reliable, automated offloading into designated bins or onto pallets. Parts can be produced on a machine that is running with very little operator involvement, or completely unattended. When the sheet is completed, the finished parts are sorted and ready to move on to the next operation.

Think Logically

As with any job, a fabricator has to have a toolbox with the right tools to get the job done. That’s what it comes down to when choosing punching as a production process. You want the tools that give you the capability to get the job done in the quickest, easiest, and most efficient manner.

Punch machines will continue to have a solid place in the manufacturing process because they can produce hole-intensive parts and parts with formed features at the lowest cost. Technology advances like built-in stroke monitoring to advise when tool sharpening is required and in which station a new tool should be inserted are making the punching process easier to use and lowering its operating costs.

Ultimately, the process that is used comes down to what the customer wants and how much it is willing to invest in producing the parts. Sometimes it’s an emotional–rather than a logical–decision.

Brian Welz is manager-punching and combination machines, TRUMPF Inc., 860-255-6000, www.us.trumpf.com.

- RoboSense is to Produce the First Chinese Multi-beam LiDAR

- China is to Accelerate the Development of Laser Hardening Application

- Han’s Laser Buys Canadian Fiber Specialist CorActive

- SPI Lasers continues it expansion in China, appointing a dedicated Sales Director

- Laser Coating Removal Robot for Aircraft

FISBA exhibits Customized Solutions for Minimally Invasive Medical Endoscopic Devices at COMPAMED in

FISBA exhibits Customized Solutions for Minimally Invasive Medical Endoscopic Devices at COMPAMED in New Active Alignment System for the Coupling of Photonic Structures to Fiber Arrays

New Active Alignment System for the Coupling of Photonic Structures to Fiber Arrays A new industrial compression module by Amplitude

A new industrial compression module by Amplitude Menhir Photonics Introduces the MENHIR-1550 The Industry's First Turnkey Femtosecond Laser of

Menhir Photonics Introduces the MENHIR-1550 The Industry's First Turnkey Femtosecond Laser of Shenzhen DNE Laser introduced new generation D-FAST cutting machine (12000 W)

more>>

Shenzhen DNE Laser introduced new generation D-FAST cutting machine (12000 W)

more>>